EIZO Interviews Victor Perez Part 2

Victor Perez - Visual Effects Supervisor

In conversation with Mike Owen, Head of Marketing at EIZO UK

The story of Victor’s career is probably the most literal example of rising from the rubble of his home in Italy to working on award winning films in London, maybe not rags to riches but certainly pyjamas to premieres. I recommend checking Part 1 first in case you missed important information around Victor’s story.

In part 2 of our interview, we delve deeper into the role of the VFX supervisor within the broader film making process.

Building Real Worlds

There are so many different roles and skills required when making motion pictures, TV shows or short films. Filmmaking is a collaborative process, a process that requires a wide array of skills, depending on the size of the production, you can have one person undertaking multiple roles from acting, writing, directing and producing but it is most likely that the team members who take on these roles do not take on roles in the more technical fields of camera, lighting and sound and even less likely that they have direct involvement in the post-production processes. There are of course numerous exceptions, stories of the transfers of skills within film-making, the shift between roles, but this is still the exception rather than the rule.

I asked Victor about how the film-making process works for him as a VFX artist and supervisor. Victor tells me, “Visual effects are usually thought to be done in post-production. Of course, in post is where you see the results, however those effects need to be designed and planned to serve the story within a budget, which is crucial for the execution of the project. When I come on board a project, as a Visual Effects Supervisor – working for the production company – I am usually called around the same time as the director, or as soon as the director has visualised the projects aesthetic elements, to start building the visual storytelling fabric of the film, together. Part of my job is to translate the director’s vision into artistic and technically specific instructions, so all departments are on the same page and working in the same direction.

Then comes the question: “How can we ‘film’ this?” and make it look, not only believable but photorealistic in accordance with the style of the rest of the film. You have to understand technical questions like what camera, lenses, lights and environmental conditions are going to be used then more artistic and subtle questions as character, style, narrative and purpose of the project, the sequence and the shot… all of that, of course, before anybody else comes onboard so you are ready. To make the impossible possible and ultimately aim for the audience to forget that it is just a “trick”.

For me the three most influential creative figures at this stage – there are many significant contributors but in the visual effects creative process we have the director, the cinematographer, and me the visual effects supervisor. Depending on the project, sometimes you get the production designer or costume designer involved in order to consider other aspects that are influential in the frame. I start in the very early stages, I have to be on set because I have to “supervise”, ensuring everything, during filming, is being executed as planned. I am designing shots way before anyone steps in front of the camera, I prepare the project for shooting and then manage the whole visual effects department, with its many professionals and studios, on set, in pre- and post-production. On set I have various duties and collaborators to ensure we get what we need. For instance, capturing lighting information, acquiring data for recreating the textures and materials on the models to be computer generated, measuring and scanning the spaces, witness cameras, references, references, and more references.

Learning to deal with all these complexities and the largest department on a film project [the VFX department], to make what’s impossible in the real world possible on the screen, has allowed me different perspectives as a writer, director, and storyteller. The point is not to aim for low costs, but for cost effective resources that serve the story, and use any limitation as points of strength: as important as what you decide to show on the screen is what you don’t show. As an artist you are not here to give answers but to ask the right questions; do not underestimate the power of the imagination of the audience. We create only 50% of the film on the screen, the other 50% is completed in the head of who’s watching. It’s easy to forget about the art when you are so worried about a budget, so learning to work within economic constraints is, necessary and healthy, but only if you embrace it. It can trigger ideas you would never otherwise imagine.

Writing and directing my own projects is the most stimulating experience as an artist. As David Fincher says: “you don’t know what directing is until the sun is setting and you’ve got to get five shots and you’re only going to get two.” As a VFX Supervisor, the final script is my “blank” page. How do I break down all the required tasks? How many people do I need? What kind of specialists do I need? You have to be sure that by the end of the filming process you have everything you need “in the can” to accomplish the VFX project. You need to know the project backwards, that’s why post-production starts before filming. In a film like, Jurassic Park, they started creating the dinosaurs before they went on set, that way you have so much information, and most importantly: the right questions. So, when principal photography wraps, the dinosaurs are ready to be added to the scene, or at least at an advanced stage, the ‘CGI asset builds’, the elements to be included in the shot.

Importance of the VFX Supervisor On-Set

We don’t work just at the end of the process, just “fixing” things in post. No way! Firstly, we design and plan shots; then capture them on set; and after, in post-production, executing and producing what is needed using computers, putting everything together, creating the final shots. The most significant part is finishing the shot, if you don’t do the work before, you might not be able to finish it, likely costing a huge amount of money, and a massive headache for many.

You can attack problems by pumping money… but this is the last resort (and you are going to make the producers unhappy… you don’t want unhappy clients, do you?), but solving them efficiently on set, when possible, is the best way. More money isn’t always synonymous with better results. Let’s fix it on set instead of “fix it in post”, every time someone says “let’s fix it in post” a fairy dies. Keeping everybody on the same page is the best way to tell a story in a collective creative medium such as cinema.

We are all subject to a budget, so we need to make it work, sometimes budgets are tighter than others, but yes, budgets are never “enough”. My colleagues sometimes find this frustrating. For me, to be honest, it’s probably one of the most stimulating aspects of filmmaking, because if you had all the money in the world, you would become lazy, because you approach creative problems the easiest way. But by having budget constraints, you are going to be forced to think, how can I fix all of that? It requires preparation, self-confidence, and a pinch of luck.

As a VFX Supervisor, you spend two to three years on a [long form] project (feature film / tv series), from the very early stages until, maybe a few days before the premiere.

In my learning process of working with creative people, every person is different in the way they approach visual storytelling breaking down its required tasks, however the most important thing, common to all of us, is to serve the story as per the vision of the director. That’s the “secret”, we are storytellers, if you start with the story, everything else is easier to explain. I always ask the director, the cinematographer or the editor, what is the story of this shot?

If the film was a book, every shot would be a sentence. What is this shot saying to the audience, I beg the director to tell me the sentence of this shot in the narrative of the story; let’s focus on what is important, then you start finding the problems and problems can be attacked in many different ways.

The critical question as a filmmaker is: “If this given element wasn’t there, could the story continue going forward and still be the same story?” If the answer is “yes” it means that particular element was there just because “it’s beautiful”, or “I like it”, or “I don’t know how to explain it, but I think it’s right” – means that element needs to go. The Director’s vision must be clear in visual storytelling. Remember: whatever is not adding to the story, remove it.

For me, one of the most visionary director who approached visual storytelling with simple ideas but huge outcomes was Stanley Kubrick, for instance, in “2001: A Space Odyssey”, the famous shot of the pen floating in space… so well executed, so close to the camera, superbly effective yet simple: the pen was attached with a little bit of glue to a big sheet of glass, you can’t see the edges because they are out of frame, and two people moved the glass creating the illusion the pen is floating. If you try to perform that shot by attaching wires the trick would be visible, not to mention the pen bouncing and the difficulties interacting with the actors… a mess. Stanley Kubrick mastered camera craft very early in his career, he started working as a photographer, so he understood the power of conveying visual ideas, and “optical” problem solving. I believe it’s essential to have this understanding to discuss visual storytelling with the director. It’s important to speak the same language to work together in the best interest of the project while keeping the budget limitations in mind, but it doesn’t necessarily means obey the restrictions but to convey your limitations via storytelling strengths.

VFX in Post-Production

In a film project, we are all visual artists: a visual artist wants to SEE things, not to talk or to hear about things. Often, it’s easier to take a picture on my phone, put it on the screen and just draw on it to explain ideas, to alter the reality of what the camera sees. I have done this so many times. When I was working as a compositor on Christopher Nolan’s “The Dark Knight Rises”, or Gareth Edwards’ “Rogue One: A Star Wars Story” my task was to pull together various elements shot on different days, with different gear, or completely computer generated images (CGI) and to put everything together in a way that seems it was shot at the same time, with the same camera and lenses, under the same lighting conditions in a photorealistic way… in other words, to hide the VFX work and make it look real. Whatever the task and the elements, you have to make sense of it in a way that it looks natural, logical, like the filmmakers arrived at the scene, just put the camera there and started shooting. What I love most about compositing is that when it’s good nobody notices it… VFX are only noticeable when they are not done well. As a VFX compositor you get all the assets and you need to make it look realistic, whether it’s shot for real or completely virtual. As the audience you just want to believe the story.

Working on a Christopher Nolan film, I understood his approach to filming, shooting as much as possible for real. It’s easy to make reality to look real, but at the same time you are limited by reality. Nolan expresses this idea in his film “Inception” when explaining how dream sharing works, describing it as “pure creation”, and I think that is, in itself, a metaphor for filmmaking. But what if reality isn’t enough, what if you want to go beyond reality, then like in “Inception” you have to bend the rules of reality and still somehow make it look realistic.

As an artist pursuing photo-realism it’s more interesting to start from something that is impossible in the real world and end with something that you would believe exists. Understand the rules of reality (physics) and human perception so you can break the rules and bend reality; the silver screen is just a distorted augmentation of reality.

When I was compositing the VFX on “Rogue One: A Star Wars Story”, the approach was completely opposite, I had something in mind, I wanted to make it real, and it couldn’t be shot. Gareth Edwards, is a talented, intelligent director, he knows how to create the vision where you can source a bit of reality in a simple and yet cinematic way, that is often enough to provide a grounded truth for the reality of a shot while allowing an artistic playground to be created on top of it.

On “Rogue One” like in “The Dark Knight Rises”, all the shots I made where in IMAX resolution, which is monstrously big, so handling all the elements was really difficult because of the huge level of detail. In “Rogue One” the shots were fully virtual, completely CGI and they were throwing reference pictures at me, “we want this to look more or less like that”. I remember Production Designer and Art Director, Doug Chiang being so specific about the appearance of the clouds in a particular shot that I researched the meteorologic conditions for the formation of those clouds, in the end the relative moisture in the atmosphere influenced not only the look of the light but also triggering other ideas like muddy puddles after rain reflecting the spaceships parked, steam off the hot engines, air condensation for the trails of the X-Wings. This might be an alien planet, but if the people can breathe air, it means there’s an atmosphere and so it needs to feel familiar, relatable to ours, while maintaining clear aesthetics, following the directors vision and most importantly: telling the story.

As an artist I cannot replicate the chaos and complexity of reality, but I know how to fake it because I know where the attention of the eye is going to be, and how the brain is going to perceive the image… and again, it’s storytelling, 50%-50% built with the audience.

©Lucasfilm

The directors goal is to make the unknown planet feel familiar, this “familiarity” starts with being believable, and photorealism is my set of rules. Once you believe what you see is real you can build a narrative on top, but if we don’t pass the suspension of disbelieve there will be no story. I think the key to the success of Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy was not Batman, but the character of Bruce Wayne being relatable, a man that is tormented by his past, his fears, his guilt… emotions we all have, these films are about characters that are like us. Of course, exaggerated but within what feels reasonable given the story, even if in reality it would make no logical sense, that is the suspension of disbelieve, we embrace the logic of the story, not the reality… and still every frame looks photorealistic. That’s why we love this trilogy because those are films about us, about being human, and answer existential questions within a framework of a story. The same thing happens in Star Wars, everything is alien, far, far away, but it’s so familiar and relatable, because the themes are universal: hope is familiar, fight for freedom is familiar, good vs evil is very familiar, so you need to get familiar so the audience can relate, no matter the setting.

When reading about George Lucas’ vision, for the spaceship combat scenes he was inspired by Second World War aerial combat footage. So, I immersed myself, going to the source, thinking: “let’s see, what I can bring to the story”, so it starts with reality and then you stylise. As a storyteller reality is just a starting point, reality in itself is boring, nobody wants to just see reality. If you want to watch reality, well, just go to the supermarket, or look through the window, it’s just ordinary boring meaningless chaos missing the point of view of a story, it’s missing the narrative. As an audience, what you want to watch is something that goes above and beyond reality, of course it needs to feel real, but photorealism and reality are two different things.

That is why for me it’s really important the image looks relatable. We are all very used to seeing photographs, and for those who love movies we are accustomed to observing reality through the lens of a camera. So, lenses are the starting point of photorealism. As a photographer I understood lenses but for “Rogue One” I did a deep study about lens artefacts, such as astigmatism, collimation misalignment (misalignment of optical elements), cross-plane defocus fringe… I spoke to lens mechanics who showed me the glass inside and how they work, this experience taught me to appreciate that the imperfection of each lens is what gives them character… just like human beings. It isn’t just about the technical aspect but the human component on every aspect of photography, that’s art in itself. The sensor of the camera captures that, the first link in the chain. Of course, there are so many other links in the visual storytelling chain but for me, everything starts with the device that captures light. I’m obsessed with technology, how technology replicates the world in an image and how technology can help me tell stories in ways never seen before.

©Lucasfilm

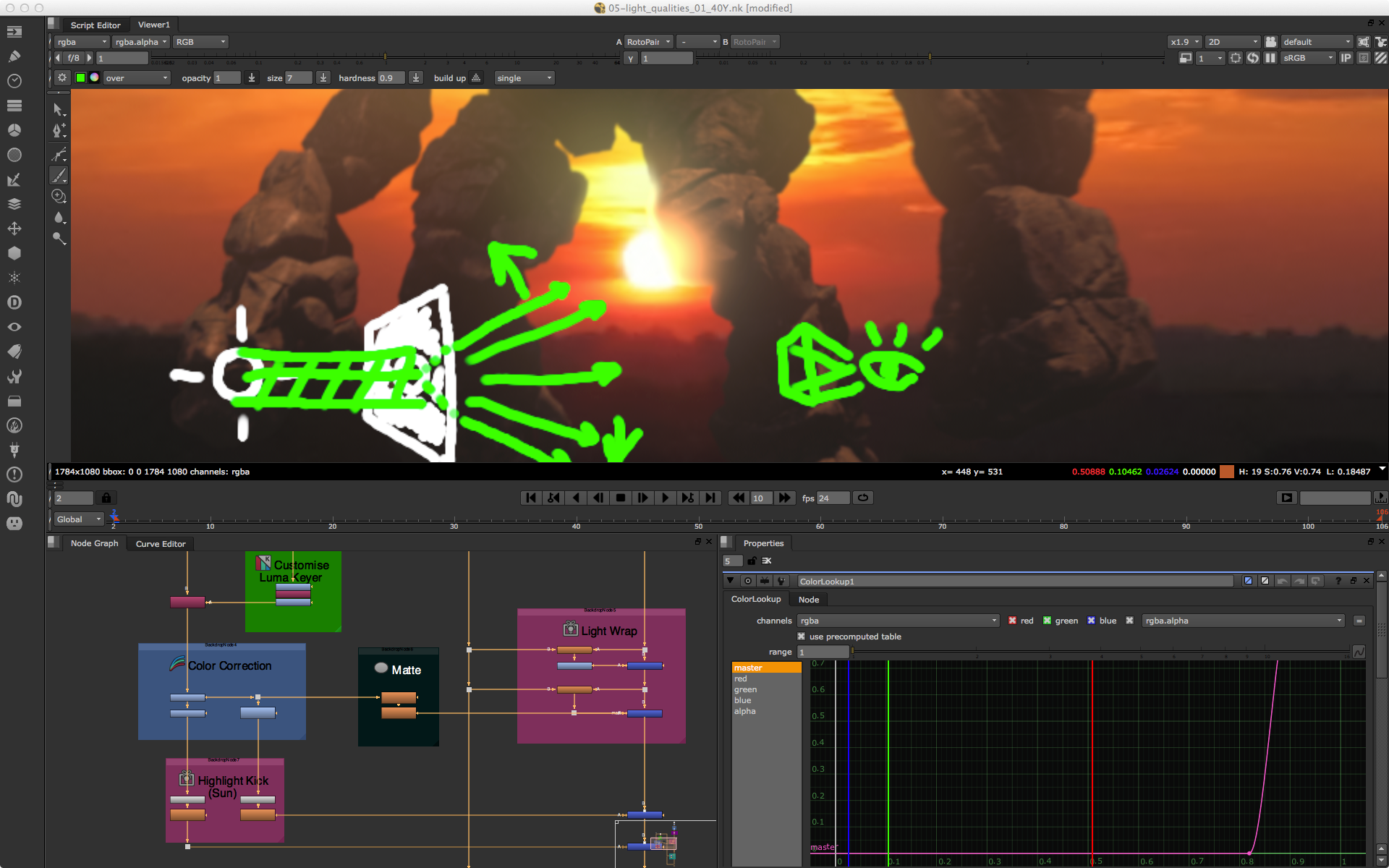

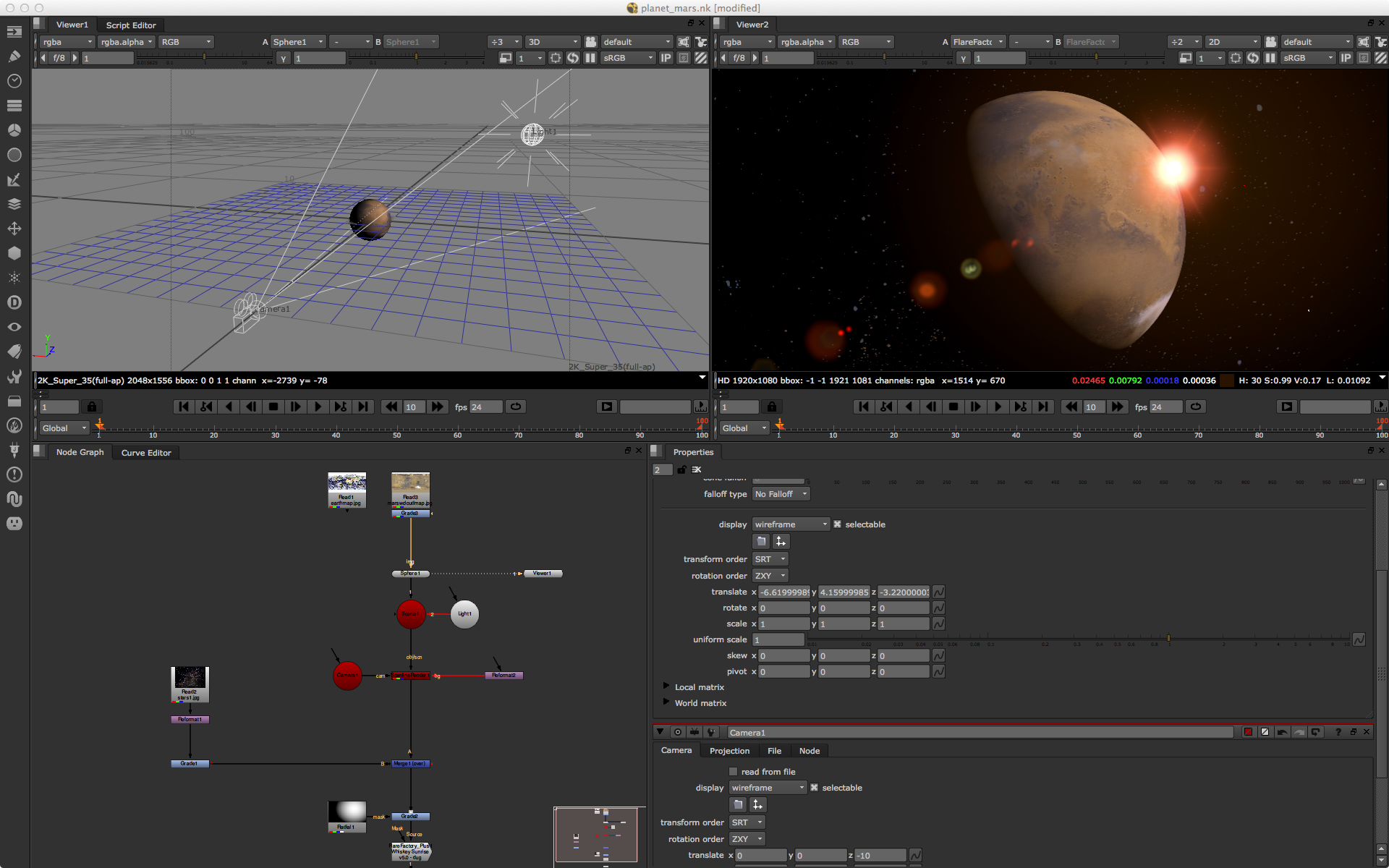

After all my experience, I believe that the most important part of compositing VFX is the ability to replicate the actual fingerprint of the image: how light passes through the lens and how the sensor or film stock will record that light. It’s an intellectual process first based on observation, analysed by the knowledge of physics and the ability to synthesise this into a simple mathematical operation for image manipulation, in the case of Nuke® [Victor’s compositing software of choice] into a nodal conceptualised mind map of operations: thoughts to nodes.

So, this takes us to the last link in the chain, how am I visualising the artwork, I need to trust and rely on the device that displays my work, the resulting image, without adding or removing anything, showing the work as it is. Which is why for displaying the image, I need to be sure that what I see is what I get. It happened early in my career, I was trying to replicate an artefact I believed belonged to the image captured by the camera, but it was actually a monitor defect. So, the original image had nothing to do with that artefact I was trying to replicate, an issue that didn’t exist in the image. The monitor needs to represent the values in the image, nothing more and nothing less. If you can get it for real, shot it for real, but sometimes reality isn’t enough, so I prefer to go beyond reality.”

At the start of my journey with Victor, we talked about the “true” art of filmmaking and there are many who think that VFX is moving away from the true art of making films, but as Victor points out, “I completely agree with this statement. There are filmmakers that consider visual effects are a modern add-on to cinema… but actually and historically visual effects have been part of cinema from the very beginning. I’m not going to mention the obvious contribution of George Méliès (‘Trip To The Moon’ in 1902; ‘The Kingdom Of The Fairies’ in 1903 or ‘The Impossible Voyage’ in 1904, to mention just a few of the dozens he produced), but milestones of cinema such as The Great Train Robbery’ (Dir. Edwin S. Porter, 1903), ‘Sherlock Jr.’ (Dir. Buster Keaton, 1924), or ‘Modern Times’ (Dir. Charlie Chaplin, 1936)… in more modern times Stanley Kubrick or Akira Kurosawa, two of the most influential directors of all time integrated VFX as an essential part of visual storytelling. So, I acknowledge there are filmmakers that consider the use of VFX makes films “less worthy”, but I definitely reject this statement of theirs, it’s just nonsense with no historical fundamental… by this rule we could also say Sound ruins movies.”

Movies will continue to develop as new technology arrives but at the same time, the primary reason we love movies is that movies and the cinema is designed to take the viewer on a journey, regardless of the genre, the journey is obviously specific to the film and the viewer, but the journey is part of the magic. Cinema is designed to transport us into the lives of the characters and the location, whether they are based in reality like Harry Potter or a galaxy far, far away, like Star Wars.

People talk about the magic of the movies, and there is no doubt that Victor and the VFX teams around the world help to build and define the magic of their worlds on EIZO monitors. Victor has been using an EIZO ColorEdge PROMINENCE monitor as part of his set up, check out the ColorEdge PROMIENCE CG1 and entire EIZO ColorEdge range.

Best Photo Editing Software in 2025

Discover the best photo editing software for your photography style – from Photoshop and Lightroom to Capture One, Affinity, DxO and Luminar Neo.

Why monitor calibration matters

Monitor calibration is essential for photographers, videographers and content creators who want accurate colour and brightness from screen to print or online.

EIZO Interviews Ellie Rothnie – Wildlife Photographer and Canon Ambassador

Award-winning photographer, Canon Ambassador and EIZO User Ellie Rothnie, talks about her journey as a professional photographer and top tips from her journey.

EIZO FlexScan FLT Product Showcase

Discover EIZO’s Most Energy-Efficient Monitor with World-First Class A European Energy Label.

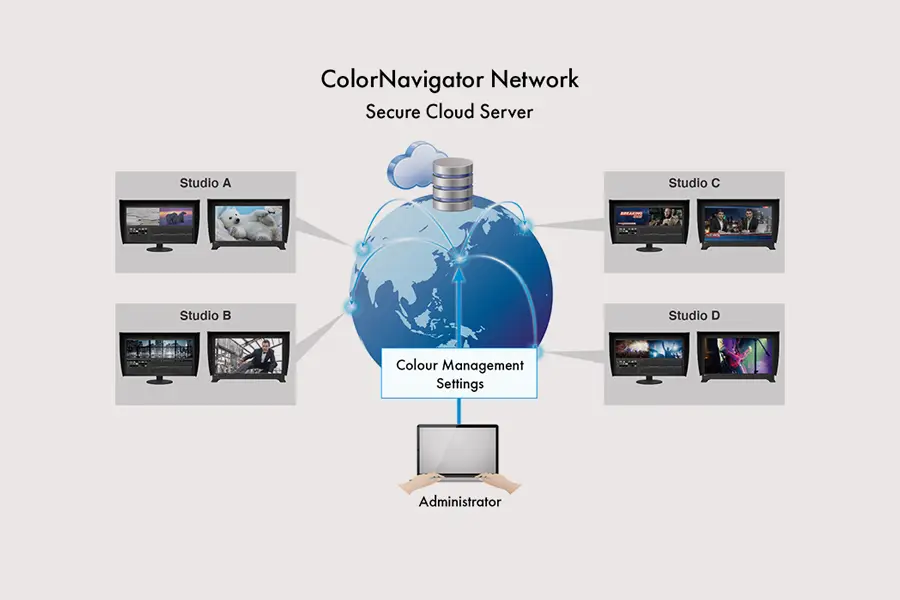

EIZO ColorNavigator Network: Solving the Colour Managed Workflow

Unlock the full potential of your EIZO monitor with our comprehensive setup guide for the EIZO ColorNavigator Network.

EIZO Interviews Victor Perez

Victor Perez is a visual effects supervisor who has worked on many blockbuster movies including Harry Potter, The Dark Knight and Star Wars.

EIZO Interviews Fifty Fifty Post Production

In conversation with Elliot Riella from Fifty Fifty Post Production about his love of EIZO and how they perfectly fit into his Autodesk Flame workflow.

EIZO FlexScan: The Best Monitors for Office Work Environments

Investing in the best monitors for office work means more than choosing a desktop monitor. It means long-term savings, improved continuity, productivity, and well-being for your organisation.

The State of Sustainability in UK IT Teams

Sustainability is front-of-mind for most of the public with 70% of people wanting to see businesses take more action on climate change.

EIZO Monitors: A Legacy of Innovation, Quality and Sustainability

Choose an EIZO monitor and do not just settle for the basic screen that normally comes as standard with the computer.

Why should I choose an EIZO monitor?

If your organisation values quality, longevity, and sustainability, you should choose an EIZO monitor.

EIZO Interviews Clive Booth

Clive Booth is a commercial photographer who has worked for many iconic luxury brands, he has photographed celebrities and shot films around the world.

EIZO Interviews Tigz Rice

Long-term EIZO user Tigz Rice, who has established herself as one of the leading empowerment photographers with an incredibly successful career shooting

EIZO ColorEdge PROMINENCE CG1 Product Showcase

EIZO releases 30.5-inch ColorEdge PROMINENCE CG1 true reference monitor with built-in calibration and advanced interfaces for efficient creation workflows.

EIZO FlexScan EV4340X Product Showcase

Discover EIZO's largest FlexScan EV4340X monitor with built-in USB Type-C dock for business professionals.

EIZO FlexScan EV3450XC Product Showcase

EIZO Unveils Its First Ultrawide, Curved Monitor with Built-In Webcam, Microphone, and USB Type-C Dock for Business Professionals.

EIZO Interviews Hamish Brown

Never heard of Hamish Brown? Well, that is probably not a surprise as it is not unusual for photographers work to be the cover image of the album or the front page of the book or magazine. If you have heard of Robbie Williams or Anthony Joshua and seen a picture of either of these British Icons, then it is more than likely that you would have seen some of Hamish’s work, but it is probably still one of the best photographers of which you have never heard.

Sustainable by Design

At EIZO believe that we have a duty to do what we can to ensure the future of our planet, so everything we do is ‘Sustainable by Design’.

Small Streams Make a Mighty River

Sustainability is becoming more important to individuals and companies alike, and if we all take a few small steps, we can all move towards a more sustainable future.